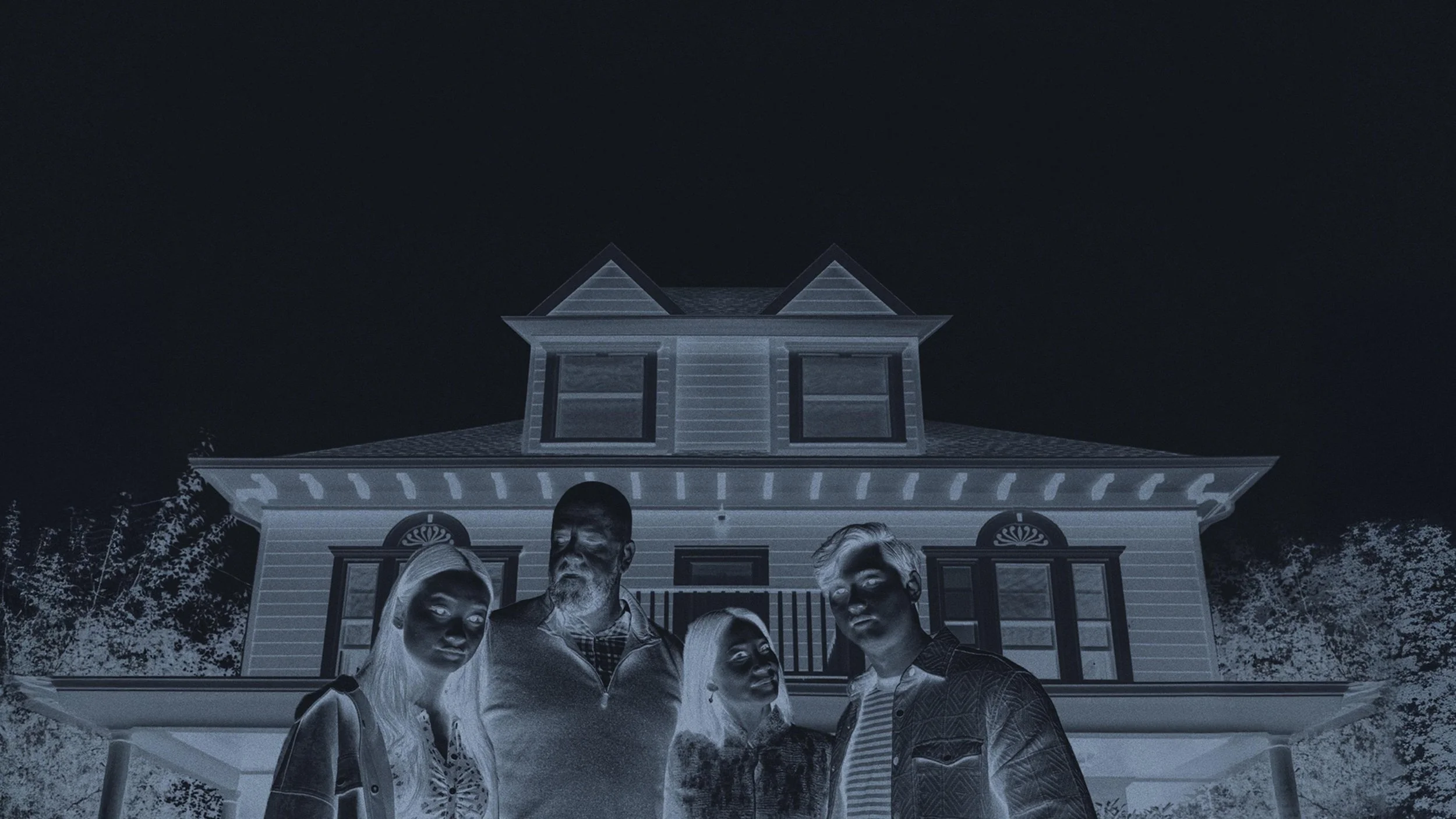

Presence

NEON

Steven Soderbergh is one of the great experimentalists in Hollywood. While appearances may be deceiving (after all he did direct major Oscar players and crowd-pleasers like Logan Lucky, Erin Brockovich, and the Ocean’s trilogy), at his core he treats each movie as a chance to experiment with either form or storytelling, finding new ways to try and move the medium of cinema forward, be it with the use of iPhones or non-linear editing.

With Presence, he reteams with Kimi screenwriter David Koepp to create something new: a ghost story shot entirely from the perspective of the phantom. Koepp himself has already tried his hand at the haunted house genre, crafting multiple chillers in his career, but for Soderbergh it is the first direct stab at the horror genre (save maybe for the psychological thriller Unsane, which featured some slasher-inspired moments).

It is clear right from the opening that Presence does not primarily aim to disturb and perturb. In a way, the film could barely be qualified as a horror film. Steven Soderbergh, ever the formalist, treats Koepp’s script as a serviceable excuse to experiment once again with digital cameras. This time around, the experimentalism comes through the film’s point of view: the titular presence haunting the house. Audiences witness the film’s events through the disembodied eyes of a ghost, floating and weaving around a house, following a family that has just moved in.

Through the wide angle viewpoint, Soderbergh purposefully keeps viewers at a distance from the lives of the characters: phone calls are one-sided, sexual encounters are peeked at through closet blinds, and the rare close-up becomes an invasion of personal space. It is a double-edged sword, because, while having the entire film play out in these long takes is impressive on a technical level, it really is hard to care for the family. It does not help that Koepp’s dialogues and narrative are mediocre at best, with the actors doing much of the heavy lifting in injecting some character into cardboard cutouts.

Lucy Liu as the mother, a successful businesswoman who might be entangled in a scandal at work (a plot line that goes nowhere), is barely present in the film, while Eddy Maday has a thankless role as the anger-prone son. On the flip side, Callina Liang holds great vulnerability and emotion as the grief-stricken daughter who is more susceptible to the ghost’s energy, and Chris Sullivan as the father completely steals the film with genuine charisma and a disarming naturalism that clashes with the poor quality of the writing.

Despite the issues with the storytelling, including a rushed ending that aims for big thrills and emotions that is not entirely earned, at 85 minutes long Presence does not overstay its welcome. The length further emphasizes the director’s intent to try new things with the camera: while POV sequences are nothing new in cinema, there are instances of fourth-wall breaks and shaky camera and whip pans that are exhilarating to watch unfold on the big screen. It is a formalist experiment through and through, a type of film that is needed to see what does and does not work by going to the extreme with certain stylistic choices. It is unlikely that such a technique will be tried again in the future to this extent, making Presence an outlier in the horror genre, yet also an interesting addition to Soderbergh’s eclectic body of work.